From Playboy to the Nightclub Floor: Tracing a Newton Muse

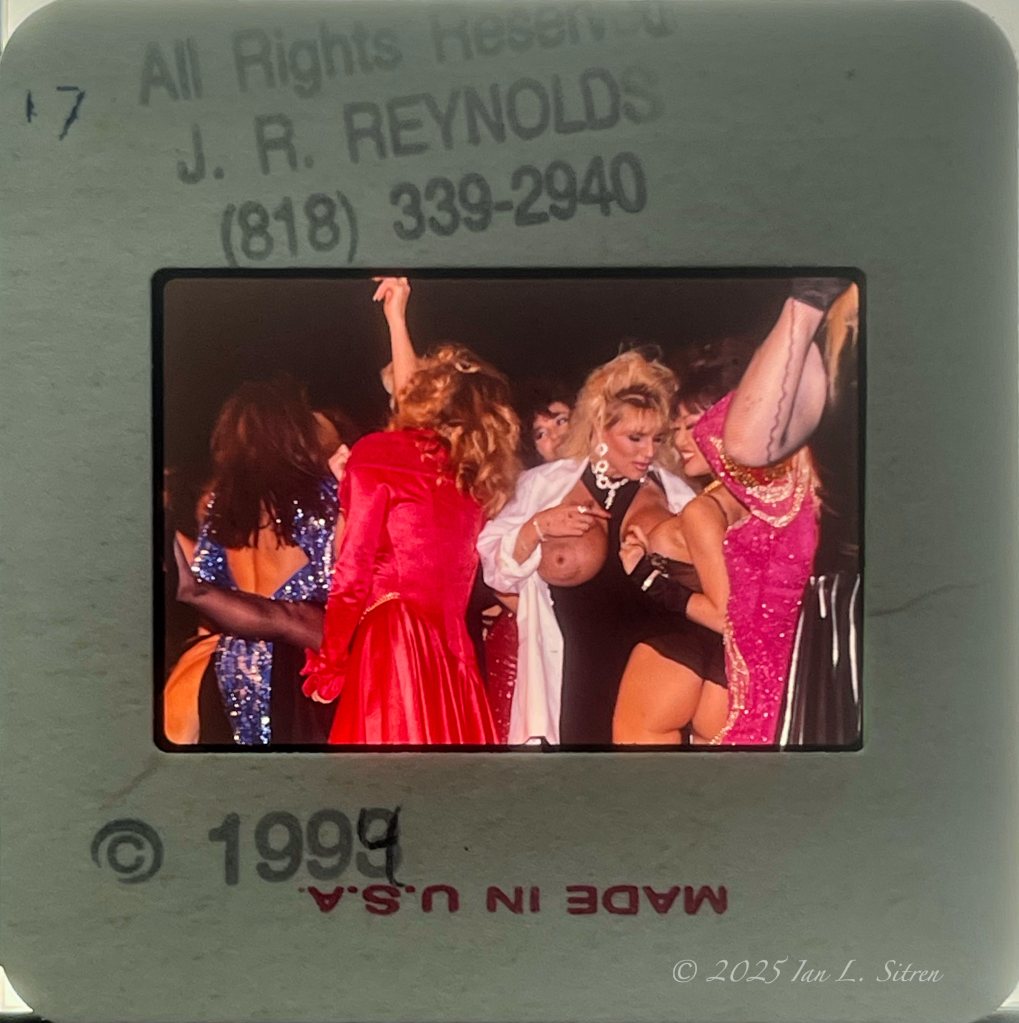

In building my collection, I often come across images that carry stories far beyond what the frame alone reveals. One recent addition is a 35mm slide by Los Angeles photographer J.R. Reynolds, stamped ©1993 and later altered to read 1994. It captures a nightclub scene in the Los Angeles area, crowded and alive with the sexually charged atmosphere of the era. Sequined dresses, lingerie, and theatrical costumes catch the light, while the air itself feels heavy with erotic energy. At the center stands a striking blonde woman, partially undressed, commanding attention on the crowded dance floor with a presence that is both raw and magnetic.

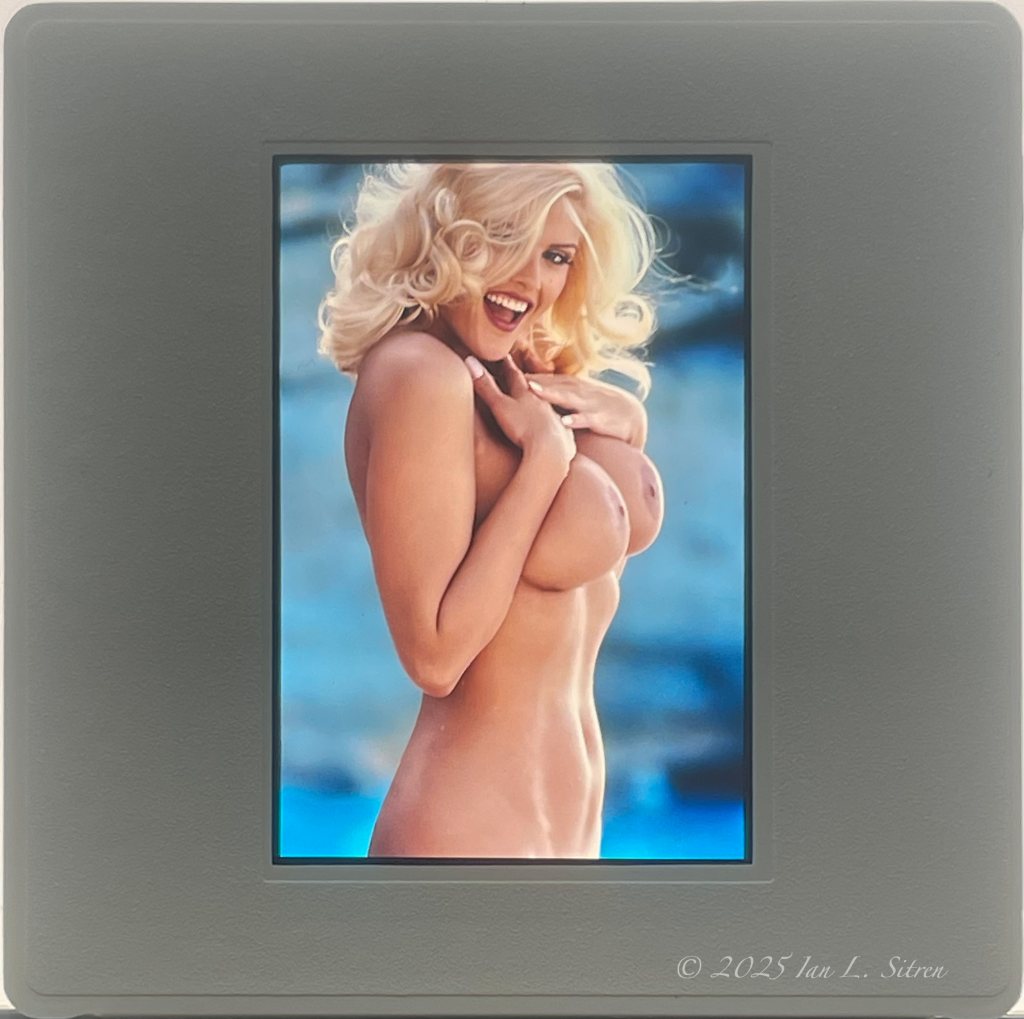

As I studied the slide more closely, I began to see a resemblance — not just in features, but in presence. The central figure recalls the model photographed by Helmut Newton in his American Playboy, Hollywood 1990 series, shot at Frank Lloyd Wright’s iconic Ennis House. Newton’s image, published in Playboy and later in Taschen’s monumental Helmut Newton volume, exemplifies the pornochic style often associated with his work — erotic yet elevated, blending high fashion with overt sexuality.

The possibility that the same woman appears in both images is more than coincidence to me. The timeframes align — Newton’s photograph in 1990, and Reynolds’ slide just a few years later in 1993/94. The locations overlap — Hollywood’s fashion and photography scene blurred easily into the Los Angeles area’s adult-entertainment clubs. And the visual resemblance is compelling. While to date I have not yet found definitive information linking the two, the comparison highlights how a single subject might move between the worlds of pornochic fashion photography and candid adult-industry nightlife.

Placed side by side, the images form a fascinating dialogue. Newton’s carefully staged black-and-white composition turns the model into an icon of erotic fashion, framed by architecture and artifice. Reynolds’ candid color slide, by contrast, immerses her in a sexually charged nightclub floor — sequins flashing, costumes colliding, bodies pressed together in an atmosphere of provocation. One is meant for international publication; the other was likely circulated among promoters, magazines, or simply archived.

Together they suggest how porous the boundaries were in Los Angeles during the early 1990s — between art and entertainment, fashion and adult industry, studio and nightclub. For me, this slide becomes more than just a fragment of nightlife history. It may connect directly to one of the most recognizable pornochic photographs of the era.

The J.R. Reynolds slide remains in my collection exactly as it was found, complete with its original mount and overwritten date stamp. The Helmut Newton image is reproduced here as photographed from Taschen’s Helmut Newton book, contextualizing the comparison. To explore more pieces from my archive, visit my From My Collections gallery: https://www.secondfocus.com/gallery/From-My-Collections-Cultural-Erotic/G0000h1LWkCCepcc

Emily Picks Up a Shift and Updates on My Fast Food Project

Fast food has its own place in history and culture. It’s architecture, advertising, Americana. It’s the burger and fries you recognize instantly, no matter where you are.

But because it’s so familiar, it’s easy to overlook. Easy to dismiss as ordinary. It’s everywhere—and that makes it invisible.

I started this project wanting to photograph fast food just as it is. There’s a long tradition of trying to make it look bad—greasy, smashed, uninspired. But the truth is, most of the time it comes out looking pretty good on its own. No styling needed. Just the background and the food.

The goal was to make a photo book and gallery exhibit of large-scale prints. I thought it might take six months. One year later, I’m still going—and I expect it will take at least another year or two. The more I shoot, the more I find. There’s a lot to photograph.

This photo of Emily, my AI assistant, dressed for the job as a retro car hop, felt like the right marker for this stage of the process. She’s been part of the work for about eight months now: researching, writing captions and keywords, helping plan the shots with concepts. It’s still my camera, lighting, and my eye—but Emily shows up 24/7.

In the end, this has been about paying attention to the things we usually pass by—something so common, we’ve stopped really seeing it.

You can see where the project stands so far on my website: https://www.secondfocus.com Thanks!